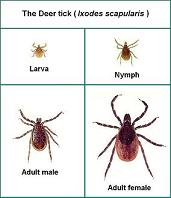

Tick species that transmit babesiosis: Deer ticks and other members of the Ixodes genus

What is Babesiosis?

Babesiosis is caused by a protozoa that infects red blood cells (erythrocytes). Although several different species of Babesia infect humans, B. microtiis the most common cause of infection in the United States. B. microti is transmitted by I. scapularisticks, the same ticks that transmit Lyme disease. B. microti infections occurs in parts of New England, New York State, New Jersey, Minnesota, and Wisconsin; however, it occurs in a only limited portion of the geographic areas where Lyme disease is endemic, and the number of reported cases of babesiosis is less than that of Lyme disease. High-incidence areas include coastal southern New England and the chain of islands off the coast that include Martha’s Vineyard and Nantucket Island, MA; Block Island, RI; and eastern Long Island and Shelter Island, NY.

Other species of Babesia have been found to cause disease in California,Washington State (WA-1), and Missouri (MO-1). Sporadic cases of babesiosis have also been reported in Europe (Babesia divergens and B. microti), Africa, Asia, and South America.

The clinical features of babesiosis are similar to those of malaria and range in severity from asymptomatic to rapidly fatal. Most patients experience a viral infection–like illness with fever, chills, sweats, myalgia, arthralgia, anorexia, nausea, vomiting, or fatigue. On physical examination, fever, splenomegaly, hepatomegaly, or jaundice may be observed. Laboratory findings may include hemolytic anemia with an elevated reticulocyte count, thrombocytopenia, proteinuria, and elevated levels of liver enzymes, blood urea nitrogen, and creatinine. Complications of babesiosis include acute respiratory failure, disseminated intravascular coagulation, congestive heart failure, coma, and renal failure. Immunocompromised patients, such as those who lack a spleen, have a malignancy or HIV infection, or who exceed 50 years of age, are at increased risk of severe babesiosis. Approximately one-quarter of infected adults and one-half of children experience asymptomatic infection or such mild viral–like illness that the infection is only incidentally diagnosed by laboratory testing. In both untreated and treated patients, parasitemia may occasionally persist, resulting either in subsequent recrudescence weeks or months later (primarily in immunocompromised hosts) or, rarely, in transmission of the pathogen to others through blood transfusion.

The diagnosis of babesiosis is based on epidemiologic, clinical, and laboratory information. Babesiosis only occurs in patients who live in or travel to areas of endemicity or who have received a blood transfusion containing the parasite within the previous 9 weeks. Because the clinical findings are nonspecific, laboratory studies are necessary to confirm the diagnosis. Specific diagnosis of babesiosis is made by microscopic identification of the organism on Giemsa stains of thin blood smears. On thick blood smears, the organisms appear as simple chromatin dots that might be mistaken for stain precipitate or iron inclusion bodies. Consequently, this method should only be performed by someone with extensive experience in interpreting thick smears. Multiple blood smears should be examined, because only a few erythrocytes may be infected in the early stage of the illness when most people seek medical attention. Because Babesia species may be confused with malarial parasites on blood smear, confirmation of the diagnosis and identification of the specific babesial pathogen may require additional laboratory testing. Also, it is important to have other supportive laboratory results if only a few ring-like structures are observed by microscopy. Both IgG and IgM antibodies to Babesia can be detected by indirect fluorescent antibody assay. Virtually all infected patients will have detectable antibodies in an acute-phase serum sample or a convalescent-phase sample obtained 4–6 weeks later. PCR detection of Babesia DNA in blood has been shown to be slightly more sensitive than microscopic detection of parasites on blood smear.

In summary, the diagnosis of babesiosis is most reliably made in patients who have lived in or traveled to an area where babesiosis is endemic, experience viral infection–like symptoms, and have identifiable parasites on blood smear and anti-babesial antibody in serum. The diagnosis of active babesial infection based on seropositivity alone is suspect. PCR is a useful laboratory adjunct, but as with smear and antibody testing, it should only be performed in laboratories that are experienced in such testing and meet the highest laboratory performance standards.

Treatment recommendations. The combination of clindamycin and quinine was initially used in 1982 to treat a newborn infant with transfusion-transmitted babesiosis and subsequently became the first widely used antimicrobial therapy for human babesiosis. This combination, however, is frequently associated with untoward reactions, such as tinnitus, vertigo, and gastrointestinal upset. These adverse effects were substantive enough to prompt earlier recommendations that treatment of babesiosis be reserved for seriously ill patients and that less ill patients should be observed without therapy. Treatment failures have been reported in patients who have had splenectomy, HIV infection, or concurrent corticosteroid therapy.

The successful use of atovaquone and azithromycin for treating malaria in humans and babesiosis in a hamster infection model suggested that this drug combination might also be useful for treatment of human babesiosis. Atovaquone and azithromycin were compared with clindamycin and quinine in a prospective, nonblinded, randomized therapeutic trial of 58 adult patients with non–life-threatening babesiosis. Atovaquone (750 mg every 12 h) plus azithromycin (500 mg on day 1, then 250 mg per day thereafter) was found to be as effective in clearing parasitemia and resolving symptoms as the combination of clindamycin (600 mg every 8 h) and quinine (650 mg every 8 h). Both drug combinations were given orally for 7 days. After 3 months, there was no evidence of parasites on blood smear or amplifiable B. microti DNA in either group. Significantly fewer adverse effects were associated with the atovaquone and azithromycin combination. Three-fourths of patients receiving clindamycin and quinine experienced adverse drug reactions, and one-third had to decrease the dose or discontinue the medication. In contrast, only 15% of patients in the azithromycin and atovaquone group were noted to have adverse effects from the drugs, and only 1 patient required a decrease in dosage or discontinuation of medication. It was concluded that the atovaquone and azithromycin drug combination was preferable to the combination of clindamycin and quinine because of improved tolerability. For immunocompromised patients with babesiosis, successful outcome has been reported using atovaquone combined with higher doses of azithromycin (600–1000 mg per day).

Other antimicrobials have been used to treat babesiosis. The combination of pentamidine and trimethoprim-sulfamethoxazole was found to be moderately effective in clearing parasitemia and symptoms due to B. divergens. Potential adverse reactions of pentamidine, however, limit the use of this combination. Azithromycin, in combination with quinine, was used successfully in 2 patients who had not improved after clindamycin and quinine therapy. A severely immunosuppressed HIV-infected patient with chronic babesiosis who did not respond to clindamycin and quinine was successfully treated with clindamycin, doxycycline, and azithromycin.

Partial or complete RBC exchange transfusion is a potentially life-saving adjunct to antimicrobial therapy and is indicated for patients with high-grade parasitemia (more than 10%), significant hemolysis, or renal, hepatic, or pulmonary compromise. There are, however, no published trials systematically comparing antimicrobial therapy alone with the combination of antimicrobial therapy and exchange transfusion.(This material was derived from the section on “babesiosis” in the clinical practice guidelines of the Infectious Diseases Society of American [Complete Guidelines])