Tick Identification and Information

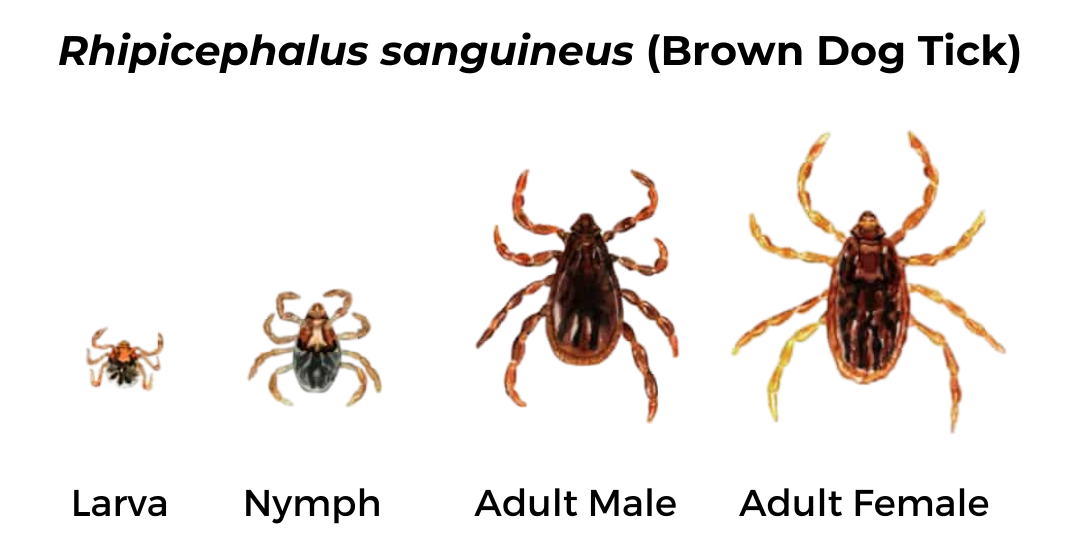

The deer tick has three feeding stages, larva, nymph and adult. Each stage feeds only once before changing into the next stage. Larvae and nymph attach and feed on blood for 3-4 days and the adult female feeds for 7 days. Adult males do not feed on blood. After feeding is completed, the tick falls off and digests the blood meal, which takes about a month before it changes into next stage. Engorged female ticks then lay eggs, about 2,000 of them, and then die. Male ticks die after mating with one or more females while they are feeding.

All of this takes place in wooded areas where animal hosts are abundant. The immature stages, larva, and nymph, of the deer tick feed upon small mammals and birds which can infect ticks with Borrelia burgdorferi, while the adult stage feeds primarily upon deer. Because mating and female feeding occur on deer, it is considered to be the reproductive host, hence the name deer tick.

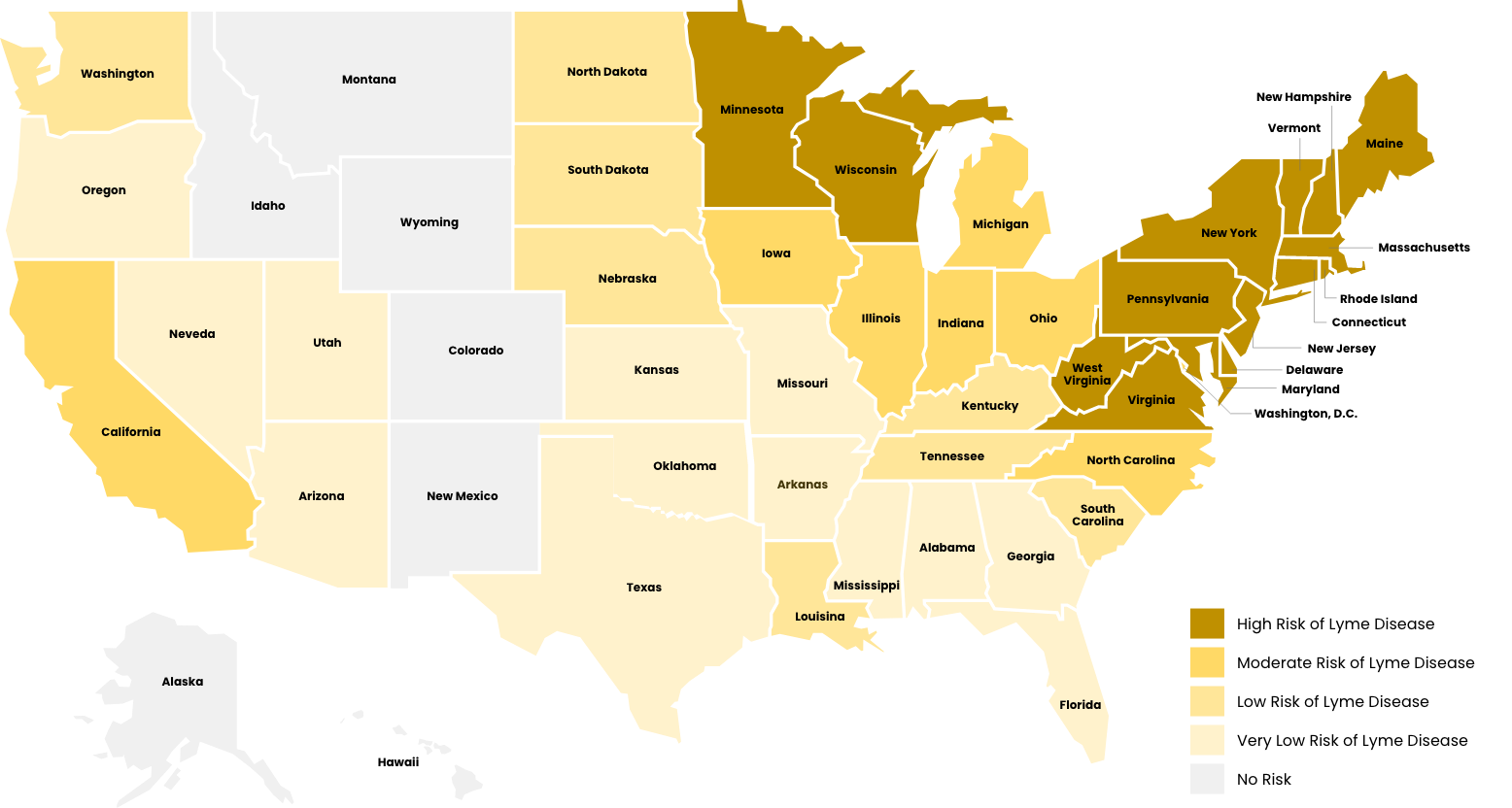

The southern form also feeds upon deer in the adult stage, but larvae and nymphs frequently feed upon lizards, which are not infected with B. burgdorferi. Thus, the risk of getting Lyme disease in the South is very low compared to the northern states.

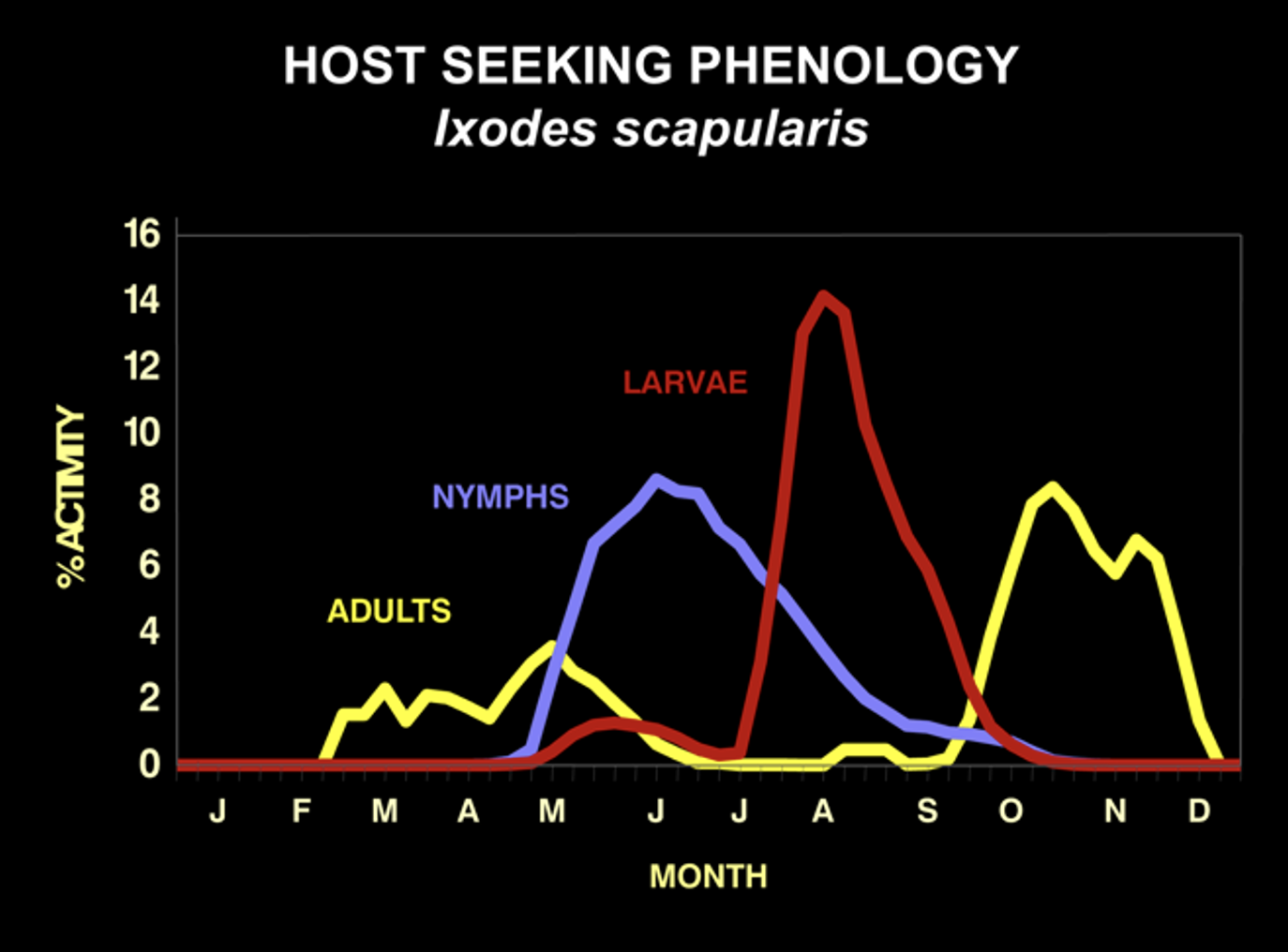

Each stage of the deer tick is actively seeking hosts at different times of the year. Larvae host-seek in August and nymphs host-seek from May to July. Adults seek hosts from late October until early May, depending upon the temperature. They cannot host-seek when the temperature is below 45 degrees or when there is snow on the ground.

The seasonality of host-seeking has important epidemiological significance as the nymphal stage is responsible for 80 to 90% of Lyme disease cases. This is because they are small and hard to see, and they are active during the summer when outdoor activities are at their peak. They commonly feed to repletion (3-4 days) on people without notice. In fact, only about 25% of Lyme disease patients recall a tick bite. This is why knowing about deer tick biology is essential for Lyme disease prevention.

In endemic areas, about 20% of nymphs and 50% of adult deer ticks are infected with the Lyme disease spirochete Borrelia burgdorferi. Bites by adult ticks do not usually cause Lyme disease because they are larger and more easily noticed than nymphs. They are also active in months with less out-door activity. But, where there are adults, there must have been nymphs earlier in the summer.

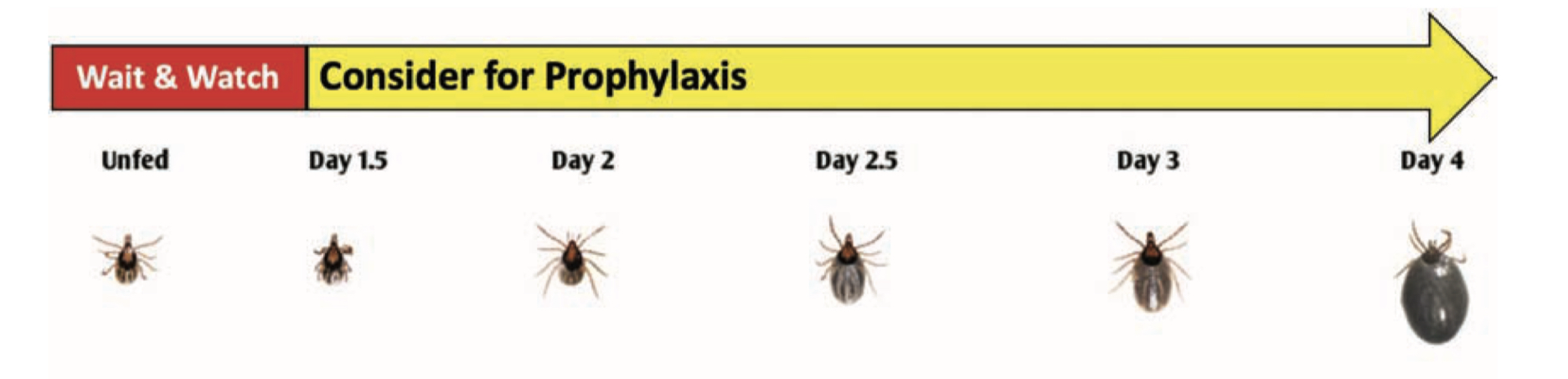

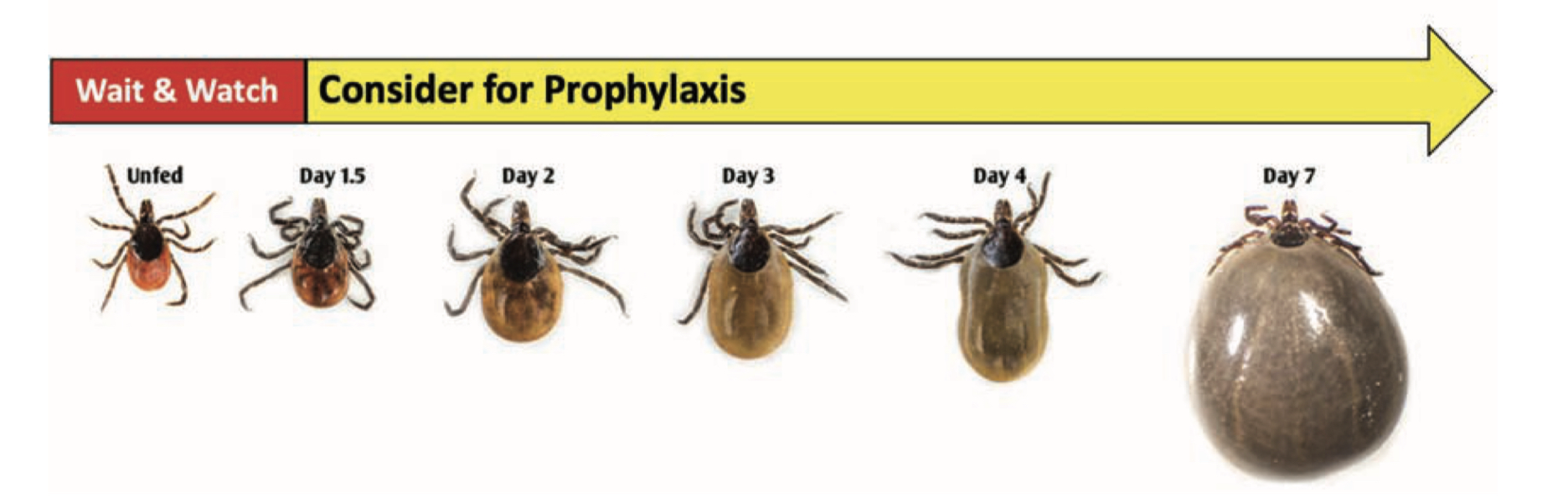

Transmission of the Lyme disease spirochete occurs after 36 hours of feeding. Finding an attached tick and removing it before that time will prevent Lyme disease. Adult ticks are usually found and removed before that time, but not so for nymphs. That’s why routine tick checks are important for Lyme disease prevention. If you find an attached tick, there are ways to determine how long it has been feeding. The chart below estimates the rate of engorgement over time-based upon animal studies. An engorgement time greater than 36 hours is considered to be risky and prophylactic antibiotic therapy is recommended.

Nymphal Stage

Adult Female

Being bitten by a tick after that time does not mean that you will get Lyme disease. There is an 80% chance that the tick was not infected with B. burgdorferi and not everybody bitted by an infected tick will get Lyme disease. Only about 2% of patients who experience a tick bite will develop Lyme disease. Watch for the development of redness at the tick-bite site. A localized redness reaction to the tick bite is common, especially if you have been bitten before. But if it expands beyond 4 inches, seek immediate medical attention for prompt antibiotic therapy. It is important to note that other pathogens transmitted by deer ticks can infect at much earlier feeding times, minutes for Powassan virus and hours for anaplasmosis, and that all stages can be infected with Powassan virus or Borrelia miyamotoi.

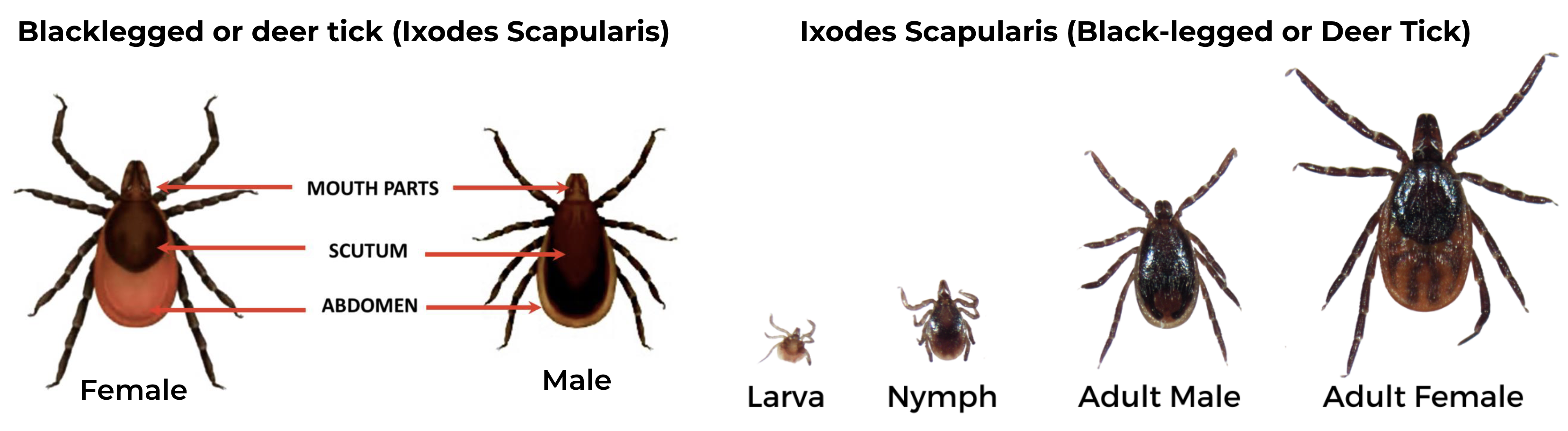

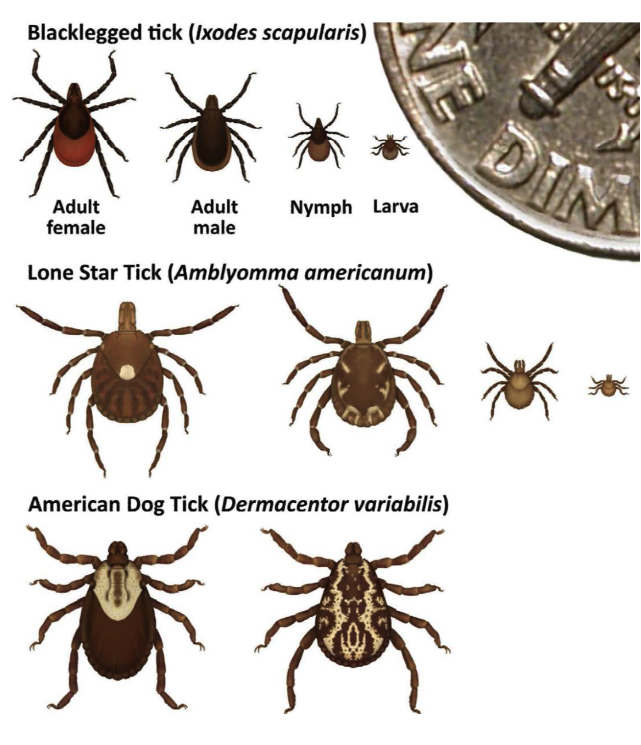

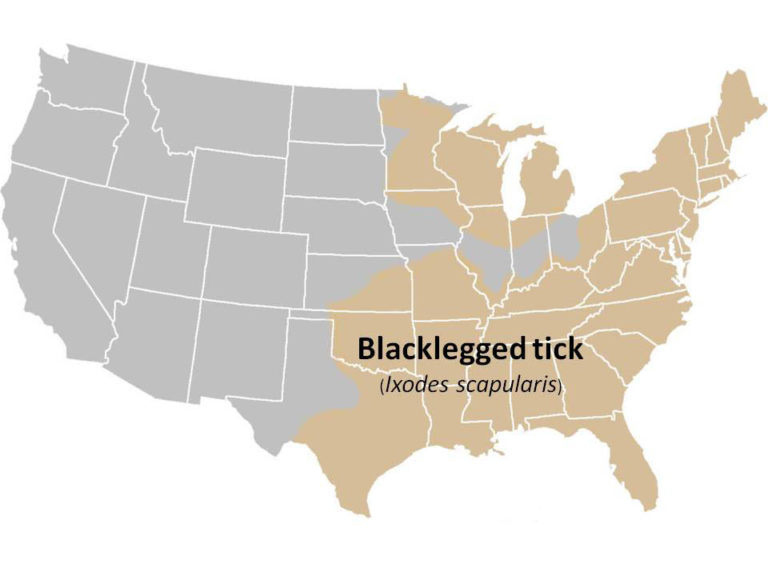

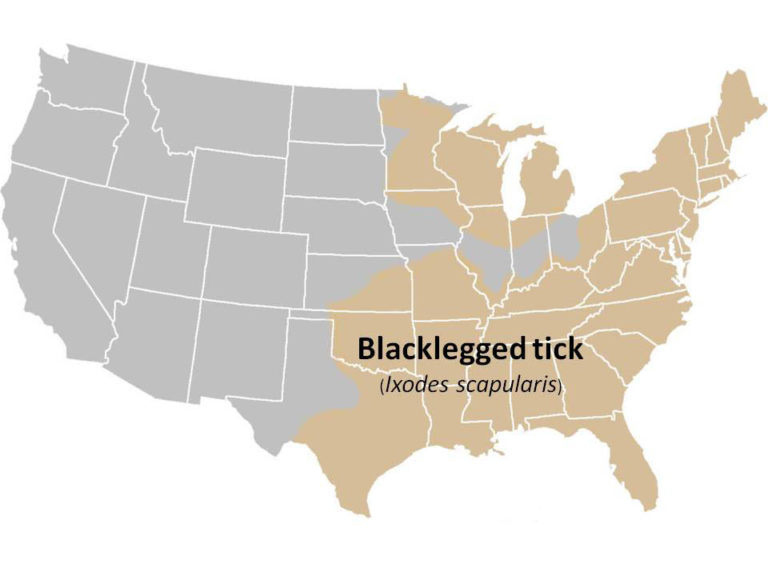

Black-legged Tick (Ixodes scapularis), also known as Deer tick

Geographic Range: Primarily in the northeastern, north-central (Midwest), and southeastern US.

Potential pathogens transmitted:

- Lyme disease (Borrelia burgdorferi and Borrelia mayonii)

- Anaplasmosis (Anaplasma phagocytophilum)

- Babesiosis (Babesia microti and other Babesia species)

- Powassan virus

Female has an orange-brown abdomen, solid black scutum and uniformly black legs. The make has shorter mouthparts, with a scutum that extends over the abdomen

I. scapularis geographic distribution

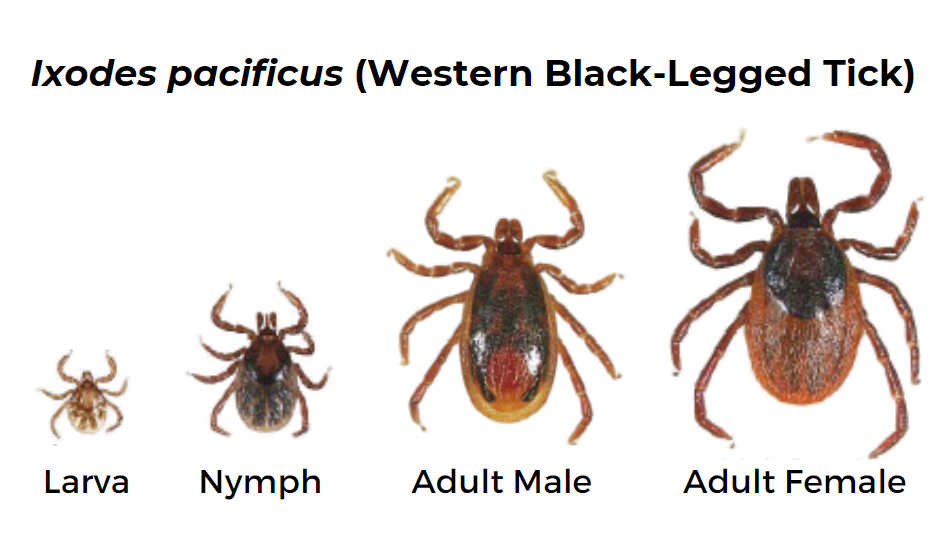

Western Black-legged Tick (Ixodes pacificus)

Geographic Range: Found along the Pacific coast, especially in Northern California.

Pathogens Transmitted:

This tick is identical in appearance to the black-legged or deer tick, but it only occurs in the western coastal states and their ranges do not overlap.

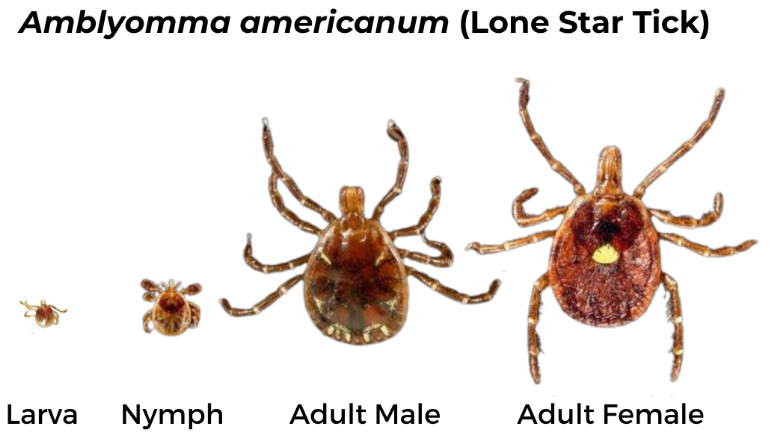

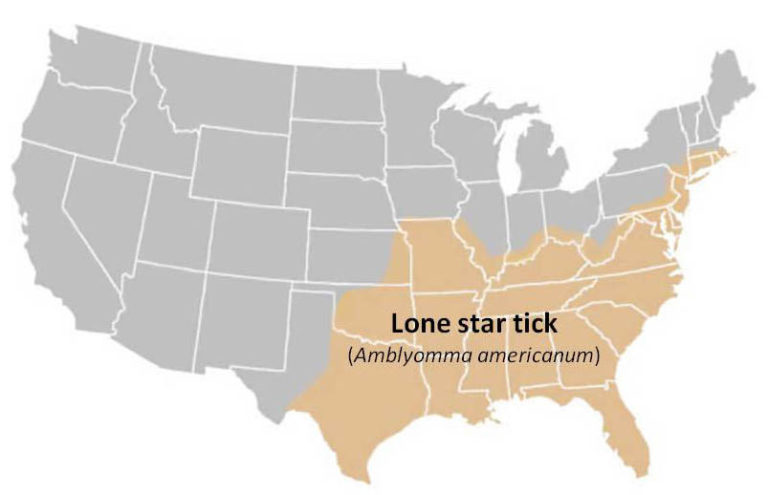

Lone Star Tick (Amblyomma americanum)

Geographic Range: Widely distributed in the southeastern U.S. but has been expanding northward and westward in recent years

Pathogens Transmitted:

- Ehrlichiosis (Ehrlichia chaffeensis and Ehrlichia ewingii)

- Heartland virus

- Southern tick-associated rash illness (STARI, but the causative agent is not yet fully identified)

- Tularemia (Francisella tularensis)

*Also associated with alpha-Gal syndrome

Female has long, narrow mouthparts, a bright white mark on the scutum and brown legs with small white bands. The male has long mouthparts, dark brown scutum covering the abdomen and white markings on the end of the abdomen.

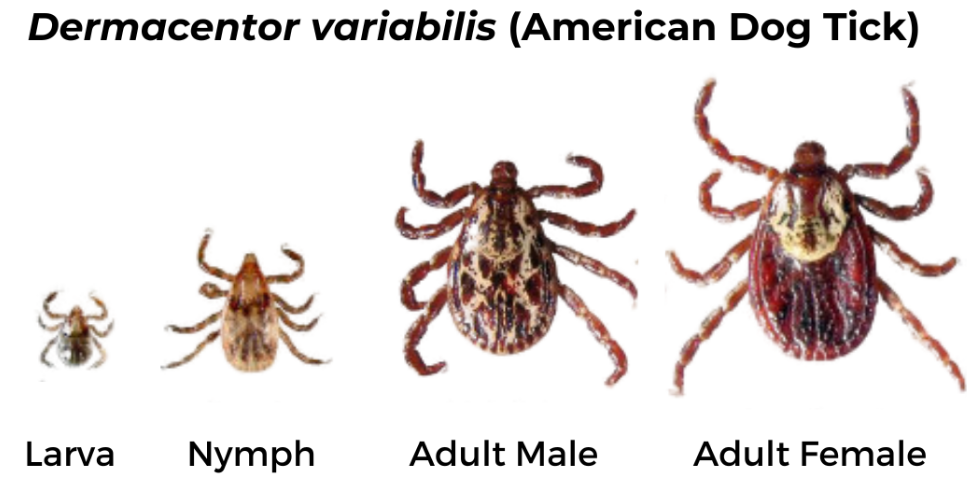

American Dog Tick (Dermacentor variabilis)

Geographic Range: Found east of the Rocky Mountains and in parts of the Pacific Coast.

Pathogens Transmitted:

Female has short mouthparts, white scutum, and brown legs with small white bands. Male has short mouthparts and scutum with white and black markings extending over the abdomen and brown legs with small white bands.

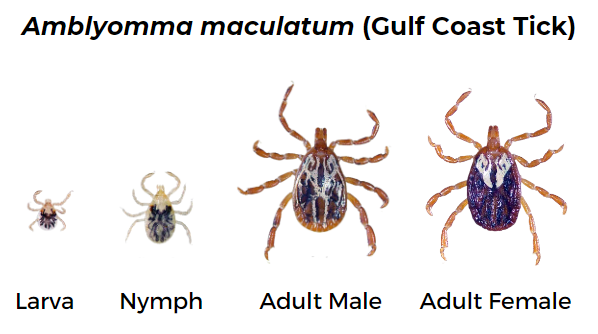

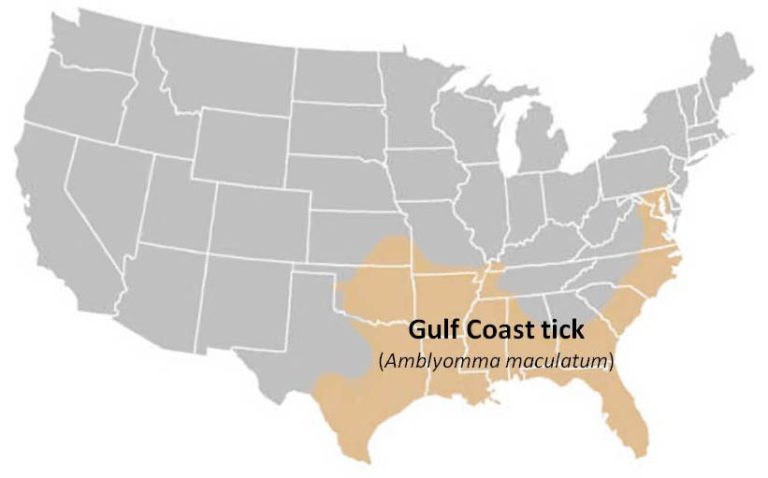

Gulf Coast tick (Amblyomma maculatum)

Female has long mouthparts, white scutum, and brown legs. Male has long mouthparts and black and white scutum covering the abdomen.

Potential pathogens transmitted:

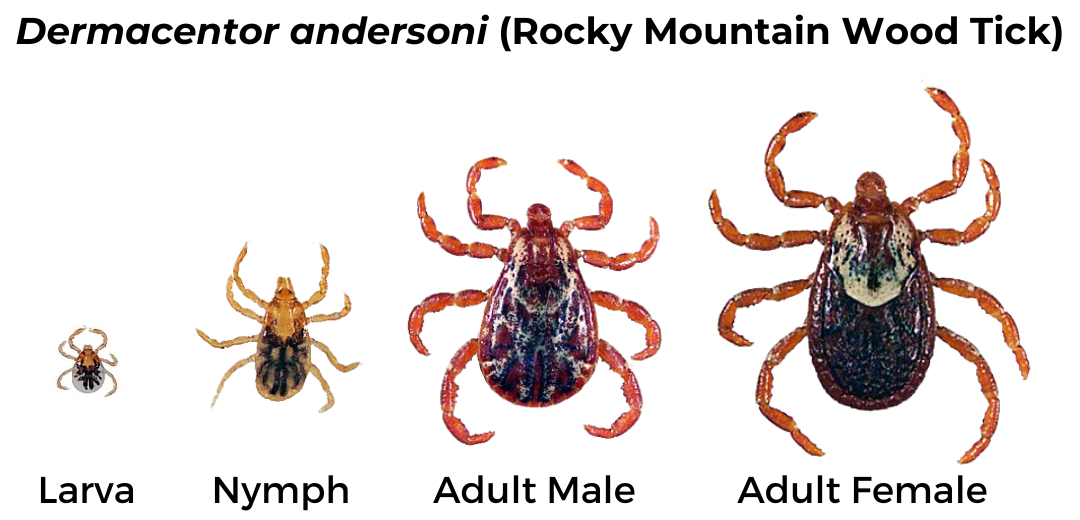

Rocky Mountain Wood Tick (Dermacentor andersoni)

Geographic Range: Found in the Rocky Mountain states and southwestern Canada.

Pathogens Transmitted:

- Rocky Mountain spotted fever (Rickettsia rickettsii)

- Colorado tick fever (Colorado Tick Fever Virus)

- Tularemia (Francisella tularensis)

Brown Dog Tick (Rhipicephalus sanguineus)

Geographic Range: Found throughout the U.S.

Pathogens Transmitted:

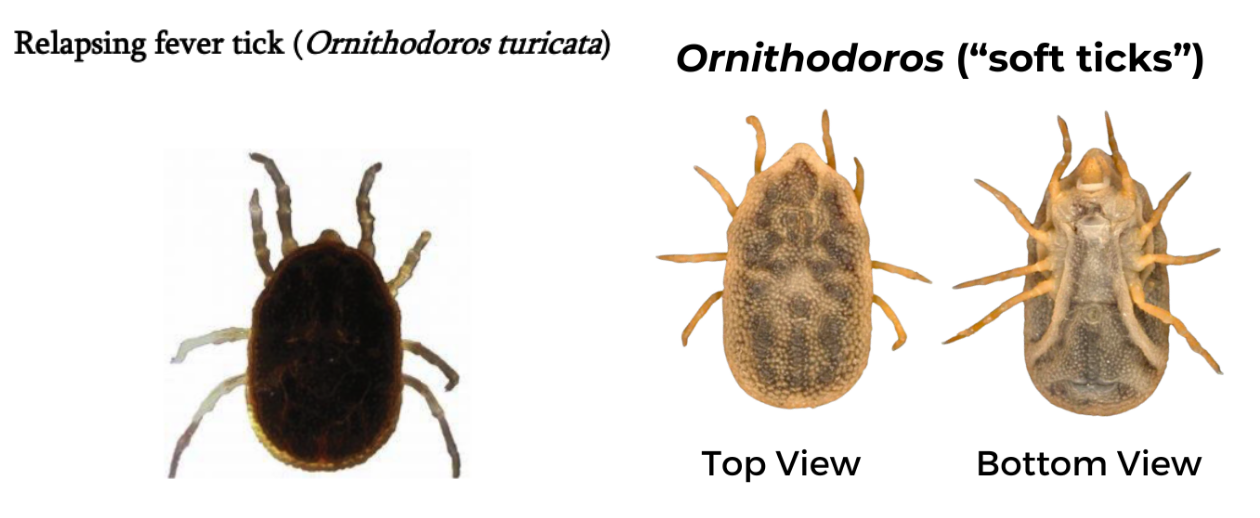

Relapsing Fever Tick (Ornithodoros)

Geographic Range: Specific to each species, but some are found in the western US, typically restricted to caves and burrows, unlike hard ticks which live in grasses.

- Ornithodoros hermsi tends to be found at higher altitudes (1500 to 8000 feet) where it is associated primarily with ground or tree squirrels and chipmunks.

- Ornithodoros parkeri occurs at lower altitudes, where they inhabit caves and the burrows of ground squirrels and prairie dogs, as well as those of burrowing owls.

- Ornithodoros turicata occurs in caves and ground squirrel or prairie dog burrows in the plains regions of the Southwest, feeding off these animals and occasionally burrowing owls or other burrow- or cave-dwelling animals.

Pathogens Transmitted:

Both male and female ticks have similar appearance. Mouthparts are hidden underneath the body and there is no scutum. Body is dark brown and legs are light brown.

Should I send tick for testing?

If I find a tick on myself, kids, or pets, should I send it in for testing? Why/why not?

Tick testing is generally unnecessary and should not be a substitute for diagnosis by a physician. Just because a microorganism is found inside a tick does not mean the tick is capable of transmitting that microorganism to a human. Remember: tick physiology is vastly different from humans.

Tick testing is not usually done in a clinical laboratory. Clinical labs must adhere to high quality control standards that do not apply to non-clinical labs. As a result, results may not be accurate and should not guide treatment decisions.

Waiting for tick testing results to make treatment decisions can be risky, especially if symptoms develop before results are available.

Just as a positive test cannot tell you if you’ve actually been infected with a microorganism identified in a tick, a negative test can give false security, as it is possible another tick bit you and did transmit a pathogen.

You can send a tick in for testing if you want, but not doing so does not increase risk of illness. You should be aware of the limitations to the information gained from doing so.

If I send a tick in for testing, does it mean I am infected with whatever was detected?

In addition, just because a microorganism is found inside a tick does not mean the tick is capable of transmitting it to a human. Remember: tick physiology is vastly different from a human, and a microorganism needs to overcome multiple challenges in order to be successfully transmitted and survive in a different host.

What should I do instead?

If you live where there is high prevalence of Lyme disease, contact your physician (within 72 hours) if you are bitten by a black-legged tick and it has been attached for more than 24 hours. High-risk bites can be treated with prophylactic antibiotics such as a single dose of doxycycline if started within 72 hours after tick removal.

Monitor for symptoms and see a physician if you develop signs of tick-borne illness in the weeks following tick removal or being in tick habitat (forests and fields, especially those with mice and deer) such as: fever, fatigue, chills, aches and pains, or rash.

Ticks can be potential vectors for illness, but it doesn’t mean they automatically are. Being proactive about prevention and prompt removal is your best defense.

Sources: